It was a great privilege to spend the first week of Black History Month learning the stories of some of BC’s Black pioneers. We celebrated many figures I recognized, such as the Stark family of Salt Spring Island, some that were new to me, and others I’ve had the pleasure of knowing personally, like the remarkable Rosemary Brown. The Community Stories exhibit, created in partnership with the BC Black History Awareness Society, “British Columbia’s Black Pioneers: Their Industry and Character Influenced the Vision of Canada” is a great place to start to learn more about the ingenuity and grit of the earliest Black settlers in the province.

This past Sunday I attended a webinar organized by the BC Black History Awareness Society and hosted by Professor Handel Kashope Wright from the UBC Centre for Culture, Identity and Education. Putting Black British Columbia History to Work: Contemporary Implications of Historical Blackness explored what Dr. Wright describes as the “absent presence” of Blackness in BC history.

Dr. Wright touched on Sir James Douglas, the first governor of the colony of British Columbia. This history was of particular interest, as Douglas’ role as governor is precursor to that of Lieutenant Governor. Douglas was born to a Scottish father and a mother who was Barbadian Creole, someone of mixed African and European ancestry. Dr. Wright posed the question: would Douglas have become governor if he had openly identified as a mixed-race man at this point in history? In the early years of the colony of British Columbia, the Blackness of Sir James Douglas was rendered absent, as part of the colonial implications of our contemporary interpretations of history.

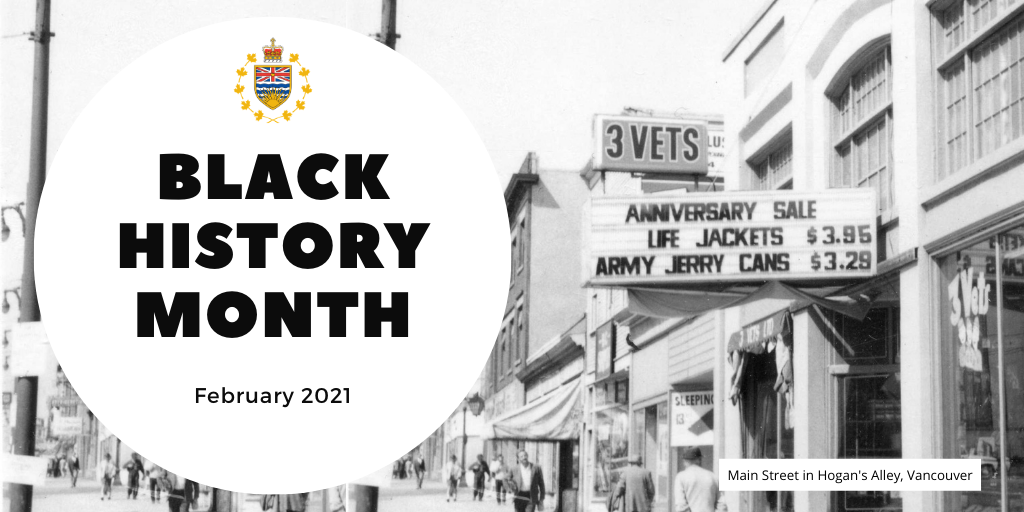

In recent years, you may have heard of Hogan’s Alley, a predominantly Black community that was located on the outskirts of Chinatown in downtown Vancouver. The neighbourhood was a cultural hub for Black Vancouverites, and also home to poor and working-class Italians and Chinese families. The racial and financial profile of this community made it an easy target for developers, who deemed it “urban blight”, and demolished Hogan’s Alley to build the viaducts that lead into the city centre.

Dr. Wright described an experience at a conference in Toronto, where he asked a mostly Black audience if they’d heard of Hogan’s Alley. While many were familiar with the Black community of Africville in Nova Scotia, few knew about Hogan’s Alley. It was a stark reminder that Black history in Canada is marginalized and often erased. As Dr. Wright described it, the Black residents of Hogan’s Alley were dispersed, and remain dispersed to this day.

All narratives will include exclusions, Dr. Wright explained, but we must take the opportunity to learn more in order to fill in the blanks. He stressed that while we cannot bring Hogan’s Alley back, we can commemorate it, and ensure that it is included when we teach history today.

This week I will highlight some of the contemporary organizations doing the work to support Black excellence in British Columbia. Some, like the Hogan’s Alley Society, bring awareness to Black history and build on these foundations through activism, while others provide opportunities for networking and development or help Black art and culture to flourish and grow.

As we celebrate the organizations that bring life to this history and support present day community work, share with me on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram if you know of a great organization that should be profiled. I invite you to explore the many opportunities to learn more about Black history with the BC Black History Awareness Society, or through other lectures, events and seminars happening this month.